Why wave period matters

A long period southerly groundswell impacted the NSW coastline last week, leading to hazardous surf warnings, yet the wave height remained relatively small.

Huge waves generated from powerful storms a long distance away, like deep lows to the south of Australia in the Southern Ocean, propagate away from these strong wind areas as swell. The longer and farther a swell travels, the smaller it gets in amplitude, but the longer it gets in wavelength and wave period (the time it takes for two wave peaks to pass a point).

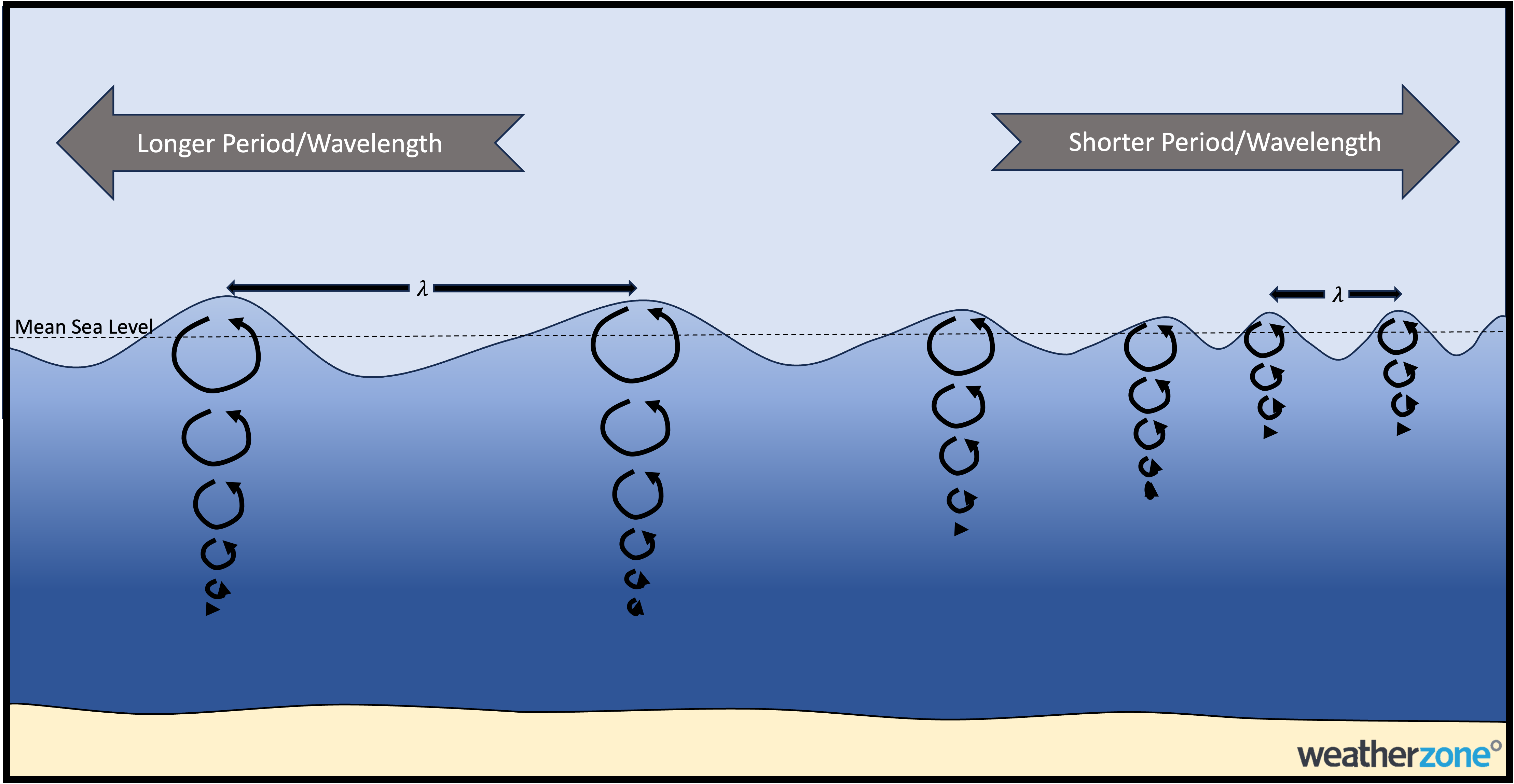

With relatively small overall energy loss, the swell energy is translated deeper into the ocean column as the period increases. This means that longer period swell, or groundswell, will carry more energy per wave, with this energy reaching deeper into the ocean.

Figure 1: Longer period swell on the left with wave energy ‘orbits’ reaching deeper into the ocean than the shorter period swell on the right.

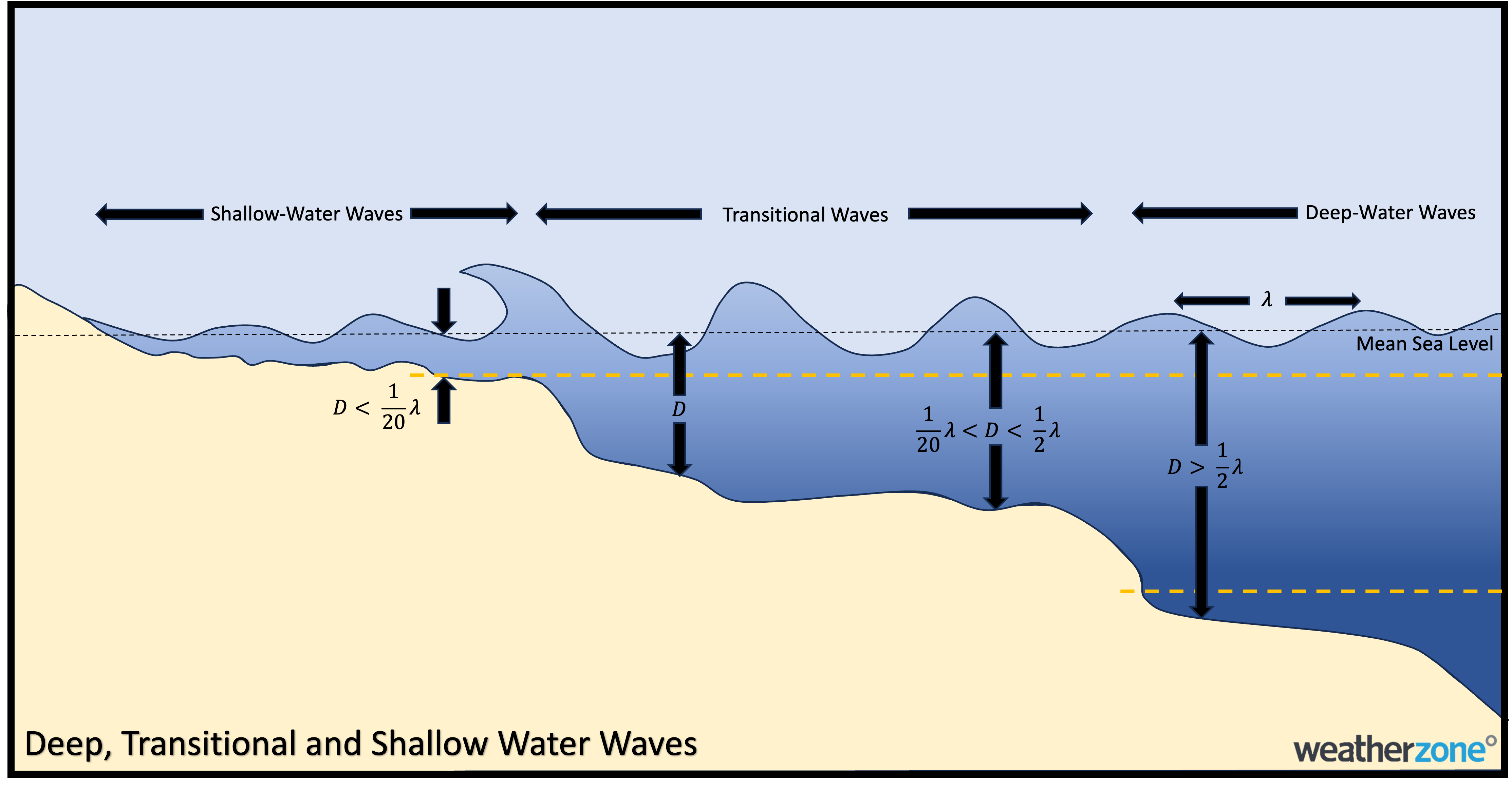

It’s for this reason that some swell with relatively small amplitude (measured as significant wave height), will be surprisingly dangerous and powerful. In a long period groundswell, offshore conditions, where waves are measured using buoys, will be fairly smooth with each wave slowly rising and dropping any boats. With a longer wavelength, the swell will begin to interact with the ocean floor at a depth of about half the wavelength (with a period of nearly 20 seconds, as seen last week, this is a depth of about 315 meters). This interaction with the ocean floor causes the wave energy to be compressed and leads to wave height to increase, also known as shoaling (this is the transitional wave phase).

Figure 2: Deep water waves transition into transitional waves at a depth of about half the wave’s wavelength, and into shallow water waves at a depth of about 1/20 the wave’s wavelength.

As a result, longer period swell will move into the surf zone with greater size than shorter period swell. The distance the swell travel also causes the waves to travel in groups, or sets, meaning that beach conditions will risk being quite calm for some time before the arrival of a set. This contrasting difference between lull and sets can lead to a false sense of security for beach goers, followed by the arrival of a very large set causing swimmers to be swept off the safety of a sandbar and into a rip. Rip currents will also be stronger with the additional energy moving into, and back out of the surf zone.

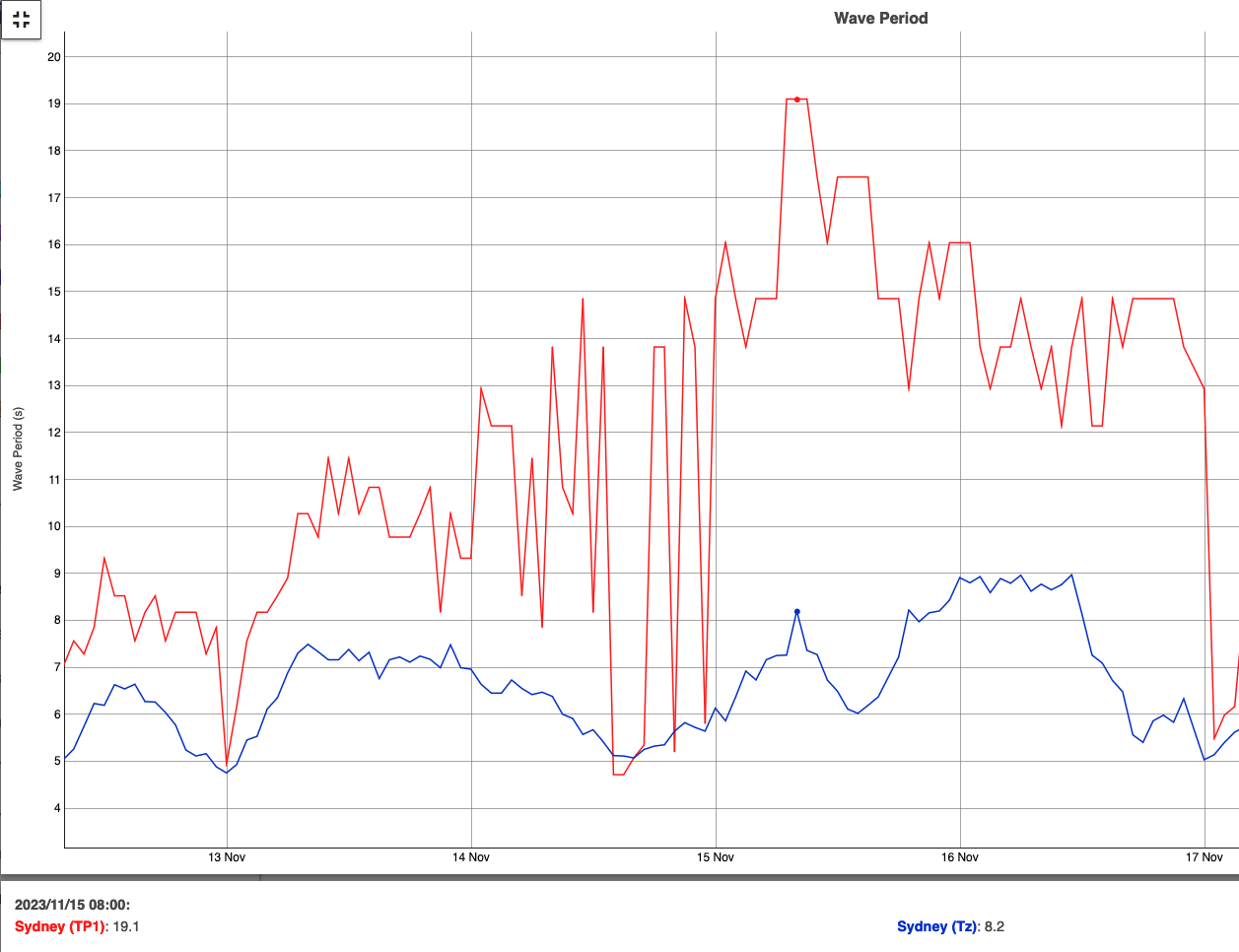

For surfers, the organisation of longer period groundswells and the larger, more energetic, waves produced are a desirable attribute. Last week, a powerful groundswell moved into the NSW coastline, with wave periods peaking between 18 and 20 seconds, leading to the issuing of a hazardous surf warning. Another long period groundswell is expected to filter into the NSW coastline late on Sunday, with maximum wave period possibly reaching 18 to 20 seconds once again. While a hazardous surf warning is not out yet for this swell, beware of larger sets sneaking into the surf zone on Monday.

Figure 3: Recorded swell period at the Sydney Waverider Buoy reaching 19.1 seconds last Wednesday. (Source: Manly Hydraulics Laboratory)