Lake Erie eeriness as wild winds create seiche

The National Weather Service issued gale warnings for the length and breadth of Lake Erie from Wednesday, November 26 through to the morning of Friday, November 28. These gales forced a wind-driven mass of water to surge eastwards, causing levels to fall at the western end of the lake and rise in the east. This is a phenomenon called a ‘seiche’, and a similar event happened recently, on October 22.

What is a seiche?

Seiche (pronounced saysh) is a word deriving from Swiss-French dialects, and was first used to describe the same motion in Lake Geneva – the back and forth oscillation of a mass of enclosed water.

If you’ve ever slid into or out of a bathtub and noticed the water sloshing from end to end – then congratulations! You’ve just created a miniature seiche. To get the same effect in a lake would require a bather larger than Paul Bunyan, so obviously other forces are in play.

Cause and effect

Seiches are basically storm surges, and they are not rare at all – just usually less noticeable than this week’s event. The October event had a persistent and consistent flow of strong, broadly westerly to southwesterly winds, gusting 40-50mph, and this week’s were much the same or stronger. The lake’s west-east orientation and relative shallowness make it rather susceptible to seiches but they can occur on the other Great Lakes.

Unlike wind-driven waves that travel across a water surface, a seiche involves the entire body of water rocking back and forth. The water level rises at one end of the lake while simultaneously dropping at the other, then oscillates back in the other direction, particularly when the wind eases or changes direction. These oscillations can continue for several hours or even days before the lake eventually settles down to its still water level. The rocking motion has its ‘fulcrum’ near Cleveland, so usually little change in water level is seen there.

Major seiche events

In extreme instances, big seiches can raise or lower the water level in the vicinity of Toledo by six feet, around Buffalo by ten feet, and in other locations around the lake’s extremities by as much as 16 feet. They can threaten flash flooding and increase shoreline erosion, and the major seiche in 1844 caused 78 fatalities in Buffalo.

In 1954 there was another notable seiche, this time on Lake Michigan, when a storm system caused water to rush towards Chicago, where a sudden ten-foot wave along the shoreline swept seven people to their deaths.

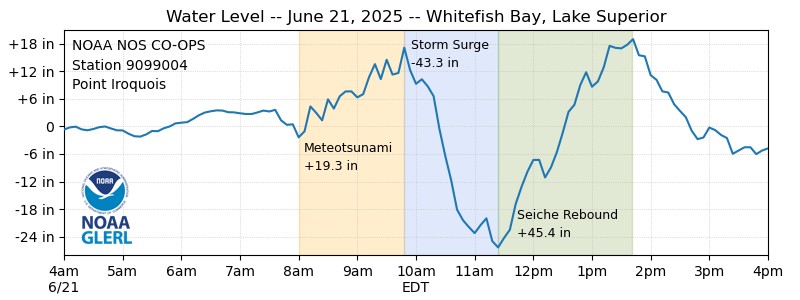

More recently, Lake Superior experienced a complicated event that included a ‘meteotsunami’ – which can occur when waves build up ahead of a storm system that’s moving at the same speed. At Whitefish Bay in eastern Lake Superior there was a nearly 4-feet rise in water levels in less than 2.5 hours. As winds turned south to southeasterly, water was pushed back across the lake to the north and northwest (a storm surge), before a rebounding seiche caused Whitefish Bay’s levels to rise again.

Image: Water level at Whitefish Bay. Source: NOAA / Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab.

Seiches can also be observed in reservoirs, harbors and swimming pools, and might be provoked more subtly by things other than winds, like precipitation, rapid changes in atmospheric pressure or seismic activity.