Earth's ozone hole is big this year. Should we be worried?

This year's ozone hole over Antarctica is one of the largest we have seen in recent years.

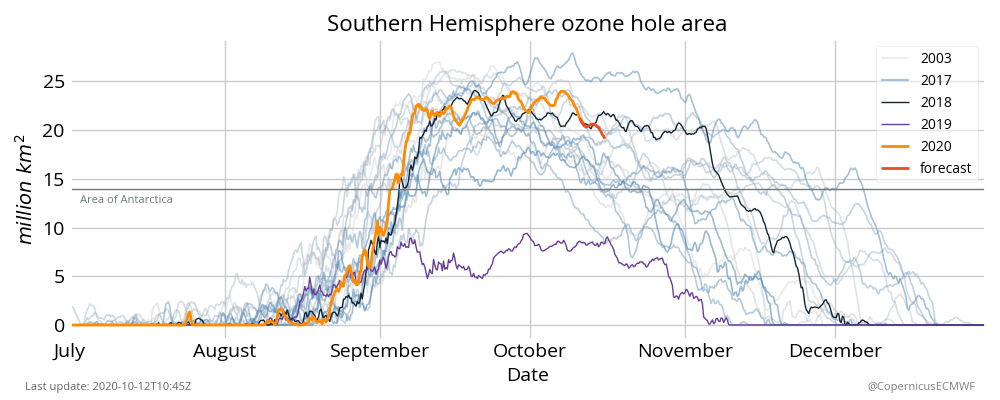

The Southern Hemisphere's ozone hole reached a maximum size of 14.8 million square kilometres on September 20th this year. This is around the same size as it was in 2018 and the equal 3rd largest it's been in the past 11 years.

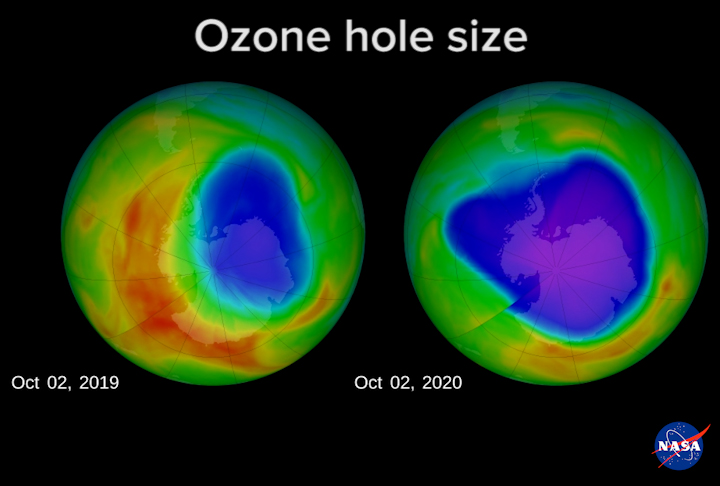

Impressively, this year's ozone hole was 50 percent larger than it was last year, although it's worth pointing out that the 2019 hole was made smaller by a rare event known as 'sudden stratospheric warming'.

Image: Comparing the sizes of the ozone holes above Antarctica in early October this year and last year. Source: NASA

This year's ozone hole is big because of a strong and stable polar vortex - meaning the band of strong winds that surround Antarctica have helped keep the upper atmosphere cold, which helps with ozone depletion.

So should we be worried that the ozone hole is big this year?

In short, there's no reason to panic.

The 'ozone hole' refers to a void that develops in a layer of ozone molecules floating around 40km above Antarctica, in a section of the atmosphere called the stratosphere. It develops every year, usually forming around late winter before peaking in late September or early October.

Image: The size of year's Southern Hemisphere ozone hole is at the upper end of those seen in recent years. Source: Copernicus / ECMWF

Ozone in the stratosphere helps shield Earth's surface from the sun's potentially harmful ultraviolet radiation. With less of it, we are more susceptible to things like skin cancer, cataracts and a suppressed immune system.

Unfortunately, humans started using a lot of ozone-destroying substances last century, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As these chemicals made their way into the stratosphere, they caused a rapid and measurable depletion of ozone. Discovering this ozone hole led to the Montreal Protocol, which is an international agreement made in 1987 to regulate the consumption and production of ozone-depleting compounds.

Fortunately, the Montreal Protocol was extremely effective and while the Antarctic ozone hole still occurs every year, it's getting smaller. Outside the polar regions, ozone concentrations in the stratosphere are also increasing as our planet's natural sunscreen replenishes.

As the last two years have shown, there is a lot of variability in the size of the Antarctic ozone hole from year-to-year - in the same way the year-to-year variability of our atmosphere can mask the overall trend of rising average global temperatures.

According to the World Meteorological Organisaton's Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project, the Antarctic ozone hole is expected to gradually close in the coming decades, with springtime ozone concentrations above the south pole predicted to return to levels seen in 1980 by around 2070.