Cloud streets – what are they and how do they occur?

During the recent Arctic outbreak across the eastern US, satellite images revealed a stunning display of cloud streets off the country’s southeastern coast.

What are cloud streets?

Narrow bands of cloud can, under certain conditions, line up parallel with the wind and take on the appearance of highway lanes – hence ‘cloud streets’. These are visible from the ground but more spectacularly from the vantage point of weather satellites.

Cloud streets are most commonly comprised of cumulus clouds, or sometimes stratocumulus, and can stretch for hundreds of miles downwind. They require an unstable, convective atmospheric environment, and so are most often seen when cold air flows over a relatively warmer surface such as a lake or ocean.

They are also possible over land in the summer months when the ground warms under a layer of cooler air. Cloud streets are usually benign, and can in fact benefit glider pilots, helping them to fly straight for a long distance; but they can also enhance convective features like lake-effect snowfall.

Image: Cloud streets observed near Grand Junction, CO. Source: Skyofcolorado, CCO, via Wikimedia Commons.

How do cloud streets form?

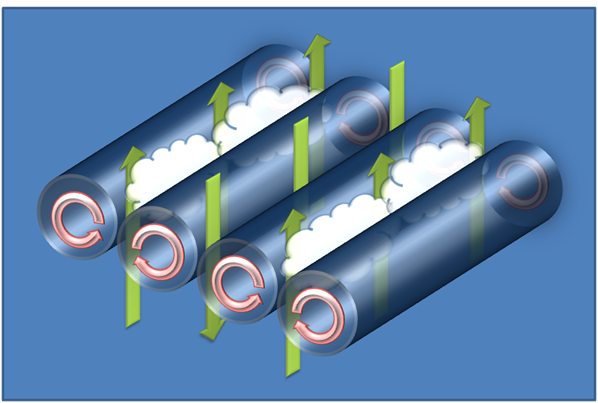

Cloud streets are the visible consequence of ‘horizontal convective rolls’ (or ‘roll vortices’) in the lowest layer of the atmosphere – a beautiful outcome of atmospheric dynamics.

The process starts with buoyancy induced by colder air moving over a warmer surface, while winds are blowing steadily at moderate speeds. Wind direction needs to be nearly constant with height through the convective layer (low ‘directional wind shear’). Air and moisture rise through the lower atmosphere until meeting a stable layer of warmer air (an inversion), and cooler air then descends on either side.

Image: Schematic representation of horizontal roll vortices. Source: Daniel Tyndall, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah.

Thus, the rising thermals roll over on themselves, forming parallel counter-rotating cylinders of air horizontal to the surface. On the rising side of these cylinders, water vapor condenses and forms clouds, while air descending on the downward side causes evaporation and drier gaps. This results in alternating bands of clouds and clear sky. The cloud streets we see are the visible tops of the rising branches while the rest of the underlying dynamics are invisible.

From space, it is apparent that the cloud formation over water begins a few miles downwind of the coast, and that’s because it takes a little while to pick up sufficient moisture. Once the convection gets going, the wind stretches clouds into their characteristic long bands, more or less parallel to the wind direction.

Do they happen in other parts of the world?

Cloud streets and horizontal cloud vortices can occur anywhere in the world when the conditions are right.

Video: Cloud streets off the southeastern coast of the United States. Source: NOAA

They are sometimes seen over the Great Lakes during cold outbreaks, and following cold fronts moving away from the coast around the world’s oceans. The Southern Ocean frequently produces cloud streets, and they can also develop over the Antarctic and Arctic Oceans.

Around Eurasia, bodies of water like the Baltic Sea, North Sea, Black Sea and Caspian Sea are favorable for cloud streets during cold outbreaks. They are less often seen over the Mediterranean.

Cool air crossing warmer land can instigate cloud streets, especially in the mid-latitudes, as long as topography does not disrupt the wind.

Image: Cloud streets over the Bering Sea, downwind of a mass of sea ice. Source: NASA Earth Observatory.

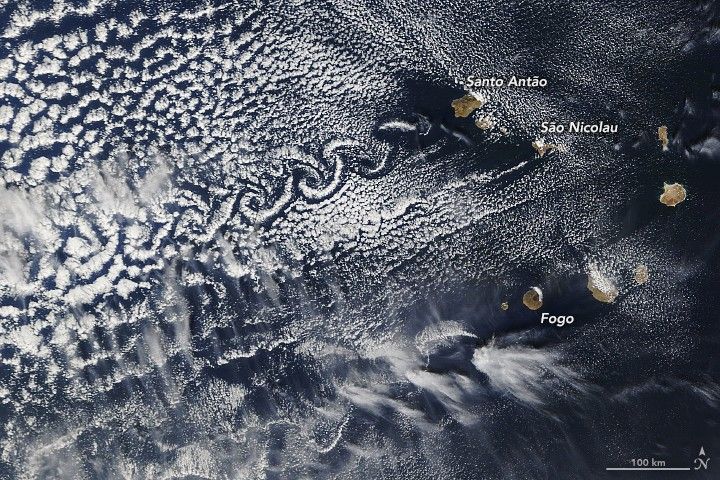

Kármán vortices

A different twist – literally – can happen when clouds encounter a feature like an island or isolated mountain. This can produce a paisley-like pattern of vortices downwind, up to 250 miles from the obstacle – a Kármán vortex street. A differently derived sort of street but just as spectacular.

Image: Kármán vortex street stretching downstream from the Cabo Verde Islands, December 20, 2020. Source: NASA Earth Observatory.