California’s Marine Layer: Nature’s Air Conditioning

California is popular among tourists for summer sunshine and heat. However, visitors often find an unexpected chilly surprise in the shape of the marine layer.

The marine layer refers to an air mass that gets sandwiched between the ocean below and warmer air above, which can bring overcast, foggy or drizzly conditions. When San Francisco’s iconic fog rolls in, you can find the piers and promenades packed with huddled and surprised masses shivering in hastily-purchased ‘Alcatraz’ hoodies. They were unprepared for the ‘May gray’ or ‘June gloom’.

How does the marine layer form?

The marine layer is dependent on the interplay of atmospheric and oceanic conditions along the coast. At root is the California Current, which transports chilly water from the Gulf of Alaska southward near the West Coast.

Even during the summer, sea surface temperatures can be as low as 50-60°F, and this lowers the temperature of the air directly above, resulting in a layer of cool, dense air right above the surface of the coastal Pacific.

Added to that, high atmospheric pressure is often situated farther offshore (associated with the semi-permanent Pacific High), causing northwesterly winds to flow along the coast of California. This results in surface water drifting offshore, only to be replaced by colder water upwelling from the deep, which cools the adjacent layer of air even further.

Temperature inversion

What’s happening offshore is not the be-all and end-all, though. Warm air drifts westwards from California’s deserts and valleys, especially during summer, overlaying the cool coastal air and causing a temperature inversion – a rise in temperature with height rather than the usual drop in temperature with height.

This inverted temperature profile stops the cool marine layer mixing with the warmer air above, while the humidity of the air mass increases due to evaporation from the ocean and by the cooling process itself.

San Francisco Bay

The marine layer most famously manifests in the San Francisco Bay Area, and 24-hour time lapses recorded from places like the Berkeley Hills and Marin Headlands can be breathtaking, looking out across a sea of low cloud or fog.

Image: Marine layer fog in San Francisco at dawn. Source: iStock_fcarucci

This is in large part due to the area’s unique topography, particularly the narrow strait of the Golden Gate, which funnels the marine layer from the Pacific Ocean into San Francisco Bay. Hot air rises inland causing pressure to fall and induce a ‘pressure gradient’ that forces the cooler oceanic air through the strait and across the city.

However, marine layers can develop up and down the California coast, near western coasts in other parts of the world and also over large bodies of water like the Great Lakes.

The nature of the marine layer

In San Francisco, the marine layer is more common in summer, when the temperature inversion is largest. It can be a few hundred to a couple of thousand feet deep to about 2,000 feet thick, sometimes thicker.

During the day it can weaken as sunshine warms the top of the layer, causing any low cloud or fog to retreat ocean-wards, only to return late in the day, overnight and into the following morning, in a daily cycle. However, if it is thick enough the gloom can persist all day.

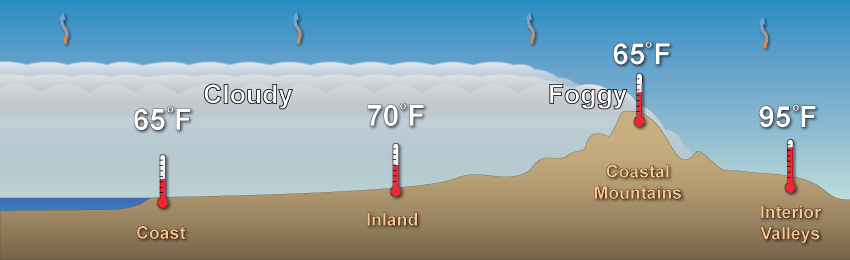

The marine layer has a significant impact on temperature. While inland areas of California can suffer extreme heat during the summer, the coast can have far more moderate temperatures – unless there is a strong Santa Ana or Diablo wind blowing from the interior. Temperatures can differ by 20 or 30 degrees Fahrenheit in the short distance between the coast and inland valleys.

Image: Influence of the marine layer on temperatures in the near-coastal zone. Source: NOAA

The marine layer also has an ecological effect, with the cool, moist air watering plant life from the lowliest vegetation to the mightiest redwood. As much as 40% of the annual water intake can be ascribed to the marine layer, while California’s vineyards can also benefit.

The marine layer is thus more than a curiosity or, depending on your viewpoint, a vacationer’s nightmare. It’s a defining meteorological feature of California's coast.